Conversation 07: Xavier Muchel

When Heather and I decided to revitalize Nox Library as a collaborative project for exploring the intersection of art and revolutionary change, there was no question that we’d bring back this series of conversations I had started during the onset of the pandemic. But now these conversations have a more focused intention; they are more concerned with how an artist’s practice, livelihood, and research engage with broader movements for a better world. For our first conversation in this new direction to be with Xavier is to pay homage to my years of friendship with him and all his contributions to Nox Library since day one. This is my favorite conversation yet because it so perfectly portrays the tone of our curiosity within Nox Library. Xavier’s enthusiasm for this project and for exploring this question with us (what is the role of art in making a better world possible?) is encouraging. It feels good to share this, and there is a definite plan to continue this conversation with a follow-up. Enjoy this first part for now.

-Danielle

xavier muchel is a non disciplined /äɴ-fäɴ″ tĕ-rē′blə/ working across the mediums of writing, drawing, performance, video, and sound. He is currently working towards his institutional stamp of approval in order to notarize his rite of passage through the inferno. He works in collaboration with Ieva lygnugaryte in a duo named Case. Together, their work investigates the poetics of life within dense metropolitan environments

Danielle Francisca is one half of Nox Library

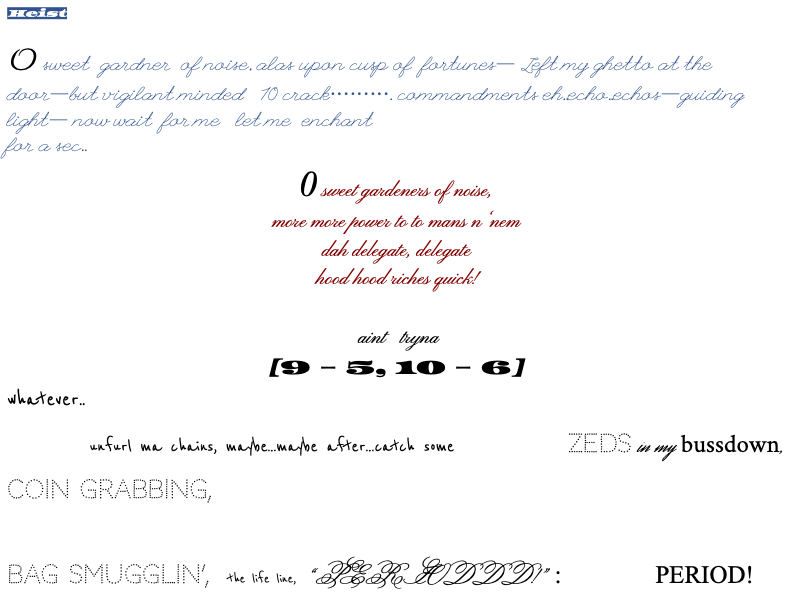

Heist page 1, Xavier Muchel. Image courtesy of the artist.

Conversation with Xavier Muchel, October 2025 (Transcript)

Danielle Francisca: I'm now recording,

So this is Danielle, I am here with Xavier Muchel, my dear friend, for the comeback of our Nox Library Conversations.

Hi, Xavier.

Xavier Muchel: Hi

DF: So you are someone who was there right from the beginning, basically, when I started Nox Library six years ago. First with a… Yeah, I think you were there at the installation I had at the house show in 2019, but you were definitely there at least for the study groups we had, for the book exchanges we had, and all of that. And now you're here again. That's kind of why I felt you were the perfect person for this, because while we're revitalizing and I am reclaiming Nox as this personal research and archival project, I felt you were the right person and artist to turn to for our first conversation. So, something I'm curious to hear from you—because you read the statement on what we're now doing with Nox Library in this new phase of it—I'm curious to hear from you what Nox meant to you back then, what do you think this sort of work means to you now, and why were you always kind of there and getting yourself involved?

XM: I think in the very beginning, especially because, you know, I had left art school and was kind of in search for a community to study critical texts with, because I just kind of needed… I needed that sort of peer group since I couldn't at that time really afford to get back into the university.

And so just having a consistent group of people, or even a fluctuating group of people that you could talk about art theory, political theory, and, you know, post-colonial theory with, and really just kind of hone in and have this group of people dedicated to really looking at a text for what it is and discussing it in a way that was, you know, not so academic—where there's no authority telling you what the text is. And that sort of just kind of works better for how I learn.

And also, I was just excited that we were all interested in art, and that we were thinking about art in this way in which it was being taken seriously.

So yeah, I think it was just important for me. It just felt very important to be a part of something, to have a group. Especially in Detroit, because it can… it can get lonely sometimes, and just having that consistency and that discipline was really beneficial for me. And it was good to organize things, too.

How do you feel about it, the “first iteration”?

DF: The “first iteration,” to me, was something super experimental. It was something I had started on my own, because, you know, I had studied art history in school and what I found that I liked so much about the history of art—and my engagement with art—was how art played a role in collective struggle, and just in broader society, and not really something that was so siloed. At the time, I felt like the art market really siloed art. There's this concept of the quote-unquote art world as though it's a world in and of itself, but in reality it isn’t. And that's kind of what I felt compelled to explore: how there is no isolated art world, that it exists as part of our world. But also, I really didn't know what I was doing. I didn't know how I wanted to explore, and that's why Nox Library was such an experimental place that tried out so many different things. But it was always extremely anti-capitalist, it was always anti-imperialist, and it was… it really had a strong political component to it, because that was really important to me, and how art engaged with those sorts of political struggles and people's movements and so forth. And I think that when you look at how artists are inspired throughout history, and even to today, it is through these frameworks and through these theories that they also attempt to engage with broader society and economic and political struggles.

Most of us are living in the world as workers, as part of a collective thing, or entity. We don't all exist in these institutions above everyone else, and so I think that there was a specific lens that I think we—I personally, but also I think I saw in my peers—really needed to explore art through, and I think with Nox Library we started to do that, and we did do that.

And now this, “second iteration” of Nox is a lot more… like if the first iteration was something where I was kind of stuck in a maze, you know, experimenting with things trying to figure out exactly what I wanted to do with all this, the second iteration is, okay, I know now what it is I want to explore and how I want to do it. And yeah, I'm excited to do that.

When I reached out to you, is that something that you thought about?

XM: Yeah, well, I was excited that we were kind of returning to thinking about the overlap of art and politics. I was excited to see that that was gonna be a focus. Because I feel like at one point, it was… I don't know, it was a super politically turbulent time, so we were mostly just focused on that kind of stuff, and I felt I was trying to figure out how to situate myself, especially during BLM, how do I situate my practice in the midst of this chaos.

For me, honestly—yeah, after leaving Detroit, it felt like painting didn't really do what I needed it to do socially. It felt like I was just making a commodity. Especially after selling to some peers before leaving, I was just like, “this feels really kind of strange.”

But anyway, to get back on track—yeah, I was just excited for another chapter in which there isn't a separation between art and politics, because I just… I think making art generally is always political, and whether or not you decide to directly address a political situation, you're still engaging in politics. I mean, just like the statement that “everything is political,” so it's… I think it was John Cage, or something, that was like “oh, I'm apolitical,” just… that just means… It just means you're not paying attention to things.

DF: Yeah, it means you're just deliberately not engaging.

XM: Yeah.

DF: If anything, to call oneself “apolitical” is to kind of take a stance that you're resisting any engagement with not just “politics,” but with a collective struggle.

XM: Totally. And yeah, I feel like Nox actually, in the beginning, really helped me with that, because at first I was engaging with political texts, and I was reading Guy Dubord or Society of the Spectacle, and I was reading a lot of these Marxist texts, but then… I was just, “oh, I'm apolitical, I don't wanna…”

But I–you know, I was super young. I don't know, it was just too much for me, and I was… I mean, I think at the time I knew that once I actually get into this stuff, it's gonna require a lot of me, and I'm gonna have to actually engage with a lot of ancestral trauma once I actually get into the politics. So I was just kind of avoiding it for a long time.

I feel during that time, 2020-2021, a lot of things were revealed about society and the way that it can potentially function, and how it can function when there's just sort of total boredom.

Yeah, I feel like Nox is really important for that part of my artistic and intellectual development.

Heist page 2, Xavier Muchel. Image courtesy of the artist.

DF: I do want to ask you about something that you mentioned, which is, you know—

You did a lot of painting, and I remember in my old home, I even had a painting of yours, and you mentioned how when you moved to New York you kind of moved away from that. When I saw you—I think last November in New York—you mentioned that you were exploring working on stuff with sound. How do you think that sort of shift in medium, or media—if you're exploring different types of channels—where did that come from, and how do you think that is kind of a reflection of this sort of exploration in some of these ideas we've been talking about?

XM: Well, I think what ended up happening was I… I moved to New York—and when I was in Detroit I really had this frustration where I really wanted to move into performance and installation and video and all these things, and I just kind of felt stagnant, and I…

I mean, it's not like that much has changed since I left, but I didn't really have the spatial capacity to paint anymore. Which, for me, I was like okay, this is good, because it's gonna force me to think in a different way.

And then I started working with my partner, Ieva. We started doing video, and performance, and when you're making video you obviously have to think about sound, so that was sort of an entry point of me starting to engage with it and have fun with it.

And then, yeah, I just sort of decided that I wanted to try it out, have some fun with it. Writing is also something that's crucial to my work, and the stuff that I do with Case with my partner, Ieva, and a lot of the foundations of our work is writing, so I have had all of this writing, like, over 8 years worth of writing that hasn't gone anywhere, and I was just like “what's the most accessible form that I could put this in?” And like, well, it has to be sound, or video, or performance, you know? And sound, depending on if you're doing music, or if you're just doing sound or video, it can incorporate all of those elements, so I think I just needed something that doesn't have these hard edges that delineate what medium is what.

In terms of how that relates to our conversation: I think that for me, I like to understand the world in a way in which you don't put these restrictions on yourself, and that could be racially, that could be gender-wise, or that could even be being a politically nuanced thinker, and things not having to fit into these niche categories, because that's not really how life works.

So I think in all of my sort of practices and collaborations, I try to emphasize not being on a border, and that feels very political to me—to always be trying to dismantle a border, you know? When you're just trying to decolonize, or not think about borders, or think about how you've been socialized to put up borders in your mind between you and another person or a social group. It's a thing that actively needs to be happening, and you actively need to be working on it within yourself.

So yeah, I think that's how it goes in my practice, is trying to open things up all the time. Whether that be thinking about the built environment and architecture, or thinking about language, or thinking about color…

Yeah, or just thinking about genre, also, and not really committing myself to a sort of genre. But yeah, I could go on and on about that, so I know that we're already over.

DF: No, that's great.

That's great. I mean, I like that concept a lot about defying those restrictions and those borders that are placed upon us from the very start of our lives. We're kind of taught these things in school, we're conditioned by society and whatnot, and I think that you're right, it does kind of create—again, going to back to the idea of silos, and I was talking about how the art world treats itself as this thing that's siloed off, and I think that especially when institutions, museums and contemporary art spaces really play on those “borders” that you talk about, things become even more deeply siloed. In one way, but then in some ways, if it's working for the people, those types of things can also give a lot of representation to certain groups, to certain people.

It's a dynamic thing, you know? These “borders” should be flexible, if… if any at all, and that's what promotes unity among people more than anything. But I also think that's what you were saying—I think that's how people, whether or not they're an artist or an intellectual, that's how someone can resonate with a work of art in kind of a super accessible medium, like video or sound.

XM: Totally, totally.

DF: Well, I had more questions about… what were you gonna say?

XM: Nothing, I'm down to answer more questions. I just am a long-winded person, so…

DF: I appreciate it. It's good.

I think that we should have a follow-up session for sure, because I wanted to get more into your collaboration project with Ieva, and maybe we could even do one session with the three of us.

XM: Yeah, I would love that.

DF: Lovely, thank you so much for talking with me about the past couple years with you, and about Nox Library, and what you think about when you think about your art.

End.

Xavier in New York, November 2024. Photo taken by Danielle.