Conversation 08: bree gant

I’ve always loved the format of reading a conversation with a full transcript. It feels intimate, like you’re sitting in on a casual exchange between two people that just met, coworkers, or maybe even your mom and her closest friend. So for my first Conversation with Nox Library, the question arose: who do I want to share that space with? Right away I thought of bree, without hesitation, but with some apprehension (being my first interview and all… especially with someone I highly respect).

I met bree in 2023, when we were both serving on the inaugural Swords into Plowshares Political Artist Residency advisory panel, but I was first introduced to their piece Wend at MOCAD in 2022. Viewing bree’s work has always felt like a meditation on life: on movement, form, object, time and the spaces that surround us. When watching bree explore their world in all its forms, I find myself in turn, exploring my own. Today, to take time to explore and acknowledge ourselves and what surrounds us, very much feels like a political act—one that is rooted in connection and care. My hope is that the following conversation will share a glimpse of bree’s thoughts and practice so that you, too, may consider what care, connection and political education looks like in your own life.

-Heather

bree gant is an artist and thinker from the Westside of Detroit. They work across disciplines, rooted in ritual and intimacy and Black Queer Feminism. bree studied film at Howard University and received an MFA Art, Theory, and Practice from Northwestern. They spend a significant amount of time binging science fiction and fantasy, waiting for the bus, and elbow-leaning in windows.

Heather is one half of Nox Library

Negotiation, bree gant

Conversation with bree gant, November 2025 (Transcript)

Heather Mawson: I know that you were away for grad school and I met you and spent time with you at Swords [Swords into Plowshares Peace Center and Gallery] before you left, and I was always very curious how your work was coming out in terms of going to grad school with intentions, and then you get there and you’re like… what? There are different things that come out through that process and I always think that’s really interesting. I’m curious for you, how was that process?

bree gant: Yea, I really loved grad school. It was great. It was very unexpected, I did not have the nightmares that a lot of people talk about MFA programs and departments, we had a very intimate department at Northwestern. But I think for me, there were two big things that going to grad school really did. And one that it offered me some perspective and distance on Detroit. I am very aware that Detroit is a huge inspiration for me and really serves as a nourishment to my practice, but I didn't understand the extent, and speaking of grad school and theory, it offered this sort of ethical distance. I don't really like the word objectivity, but it gave me some distance and perspective to really look at my relationship to the city and how it informs my practice. It also offered me or introduced me to performance studies. I love books, like I'm in my studio now surrounded by books, but I never really considered myself a theory girl, and being introduced to performance studies and a lot of new writings on it—from Black Feminist writers and authors—really shifted the way or expanded the way that I held and regarded my own creative practice…

HM: Because your undergrad experience was focused in film, is that right?

BG: Yeah, I was at Howard over a decade ago, forever ago, and I went for international business, but ended up studying film, which really changed my life and affirmed so many things for me. But it was…it was definitely more production focused, although I had a lot of really great discussions and resources with professors.

HM: Around this idea of film and the image, and the idea of capturing image in film, then what you were talking about in terms of performance—looking at your thesis work, Negotiation, there’s a lot of play with that. Was there a live performance with that piece, or was it all through the form of video?

BG: Right? That is the question. So I think I consider that piece to exist across performance and the video installation. What was exhibited during the thesis exhibition was just the video installation, but I also consider video installation to be a performative work in itself. It was installed on a wall that was built into the gallery, as opposed to projected onto the wall. It was multi-channel on two sides of that wall, so you had to walk around it to experience the whole thing, and the viewer becomes a part of the performance. There were recordings of these gestural performances that I did on campus in public space, like in front of the library on the quad, as well as in my studio. So there's a lot of players to it, and it happens across time. I am interested in complicating this conversation of performance and lens media.

HM: Speaking of performance, at the top of my mind and what was brought up for me when looking at your work was the Fluxus movement. An artist that I really respect was a part of the Fluxus movement, Allison Knowles, recently passed away, so I was just revisiting her work and it’s at the top of my mind. It made me remember that I have a real soft spot for the Fluxus movement, because it bridges or collapses art in everyday life. But with that being said, I do recognize that this kind of bridging art in everyday life has always existed and that it didn't start in the 1960s with the Fluxus movement, that people have always found ways to bring everyday objects, themselves, and space into a creative sphere. One example I was thinking about with this in mind was rituals, and how much of creating rituals for ourselves actually uses everyday objects, and I see that a lot in your work, in terms of bringing everyday objects and yourself into your work.

I'm curious how you think about that, that kind of space, about the everydayness of your work, whether it be riding a bus, because I know that so much about your practice, or just the inclusion of body and movement?

BG: Yeah, absolutely I do often. I consider my work to be rooted in ritual and research, and I think those things are very entangled, and I intentionally entangle them in my practice. I really look up to and feel in conversation with Katherine Dunham and Zora Neale Hurston. They were both anthropologists and artists and didn't compromise on that relationship by trying to fit themselves into either the academy or the gallery. I think that they found the marriage between ritual and research through performance and Black Feminism and this space, that was where they were uncompromising in their relationship to how the institutions they worked with and their artists relationships informed the very work that they were doing.

When I hear you talking about and see in my practice this everydayness of art. I think, you know, there is the Western notion of art being relegated to the white cube which was in an effort to control culture, control narrative, and kind of craft and care for this space of elitism. I think that we can have really… I hate the word rigorous, but I'm still looking for language around it. I think that we can have really rigorous, really thoughtful, really critical conversations around art without making these class distinctions between what it is. And that's what this relationship to every day does for me and my practice. I do often talk about depending on the bus in the Motor City as being not just social performance and a research site for my practice, but also land reverence and political education.

HM: That was a question I wanted to ask you about, how do you view it (riding the bus) as political education specifically?

BG: Yeah… I didn't depend on the bus growing up, I took it sometimes with my grandmother. I took it more often in high school, when I just wanted to hang out downtown between getting out of school and my parents getting off work. But after I graduated from Howard and moved back to the city, is when I actually had to depend on the bus, especially as an everyday commute to work or to hang out in the evenings. And it was such a transformative time for me, as well as for the city. This was around when the city filed for bankruptcy. So the spaces that I was moving through, and the way that I was moving through those spaces, there was such stark differences. In one way, what people were saying about Detroit and that it was being revitalized and funded, and that it was so much better, when really it was being art washed and there was funding for murals, there was funding for condo developments, you know, there was funding for particular things and for particular groups of people in the city, but not for basic necessities like public transit. So it was this mental experience of understanding how these conversations and brandings were working for gentrification in the city, but it was also a very visceral physical experience of the space, of waiting for the bus for an hour to get downtown to these new bars and shiny events that were having these investments with people who didn't know how to move in our city.

Negoation, bree gant

One of the things I often talk about with gentrification is that there is a violence in people coming to your home space without a self awareness, and that really changed the way I moved in my practice and helped me understand my practice as a performance practice, and not just as a working through the lens, but a physical labor and choreographies of power in the city, and that is kind of deeply rooted place of where Negotiation came from. It is this black feminist naming of the ways that we have to navigate social positionality and the work my thesis piece, Negotiation, kind of renders visible with this conversation between dance, film and architecture, of how those aren't just mental, emotional labors, but also physical labors of trying to negotiate what it means to move through the world and moving around these various narratives of who you are and how you're supposed to move? Yeah, I don't know if I answered your question…

HM: No, you did. You definitely did, what you were talking about in terms of gentrification, you know, and the activity of you riding the bus at a point, doing that for leisure, for fun, to get to places after school but then there was a point when you used it for utility… I don't know if that's the correct word… just for like, for necessity. And during that time seeing the city change and witnessing that, and witnessing is something that comes up so much in your work. When I think about witnessing, I feel like it straddles two different spaces. You can bear witness to something to speak truth later and there's agency within that. But there's also this part of witnessing that you don't have control over, that one doesn’t have a choice in and I think when you bring up gentrification in the city, that's one example. But also one’s positionality within society. Many don't have a choice to bear witness to one's own experience in your own body moving through a society that is rooted in white supremacy, for example. I was curious if you had thoughts around that, and how you see witnessing in your work.

BG: Yeah, very much. I talk about witnessing a lot when I talk about performance. For me, performance is a practice of witnessing and listening to self and other, and again, particularly interested in and informed by Detroit, because I think witnessing functions differently. It's that spiritual legacy of witnessing in the church and just bearing witness to fellowship to God, to how people relate to each other and their divine experiences. And then there's this conversation or distinction between witnessing and surveillance and a lot of traditional Western performance seems to fall closer to surveillance and particular separate power dynamic between the viewer and the performer, and growing up in Black space, that distinction tends to be complicated or blurred. The line between performer and viewer is more about being a part of the performance as a viewer and as a witness, rather than being something separate and walled off in this like surveillance state.

So I think it's interesting that you say you don't have a choice. It's like we do bear witness to a lot more, that idea of double consciousness, triple consciousness and multi locality. Like we see the system and are outside of it, so we experience it in multiple ways. Moving through gentrification, especially in a Black city, it highlighted for me experiences of madness and neurodivergence, and that's also a big thing that informs my practice.

I really love one of the core articles that stuck with me in undergrad was an essay written by bell hooks on theorizing as an action. A lot of what she got from Black Feminism was understanding that she wasn't crazy. Like, that is a thing. Once you get into a room with other folks who are going through things the same as you, you're like, oh… I'm not crazy. These things are happening and they shouldn't be happening, and I'm not the only one going through this, but it's still it's a maddening situation when you have to experience something that you're told isn't happening, and that's part of that. What I think you're articulating with this isn't a choice, like there are people who get to choose to not see what's happening. They get to choose, to look past, look beyond, see other things, and we don't, especially as a long term resident of Detroit, as a Black queer, non-binary femme, there are things that I bear witness to, and it's not just visual, which is another root of my practice—embodied witnessing. Our bodies witness a lot more than sometimes our mind acknowledges.

HM: That strikes a chord with me only because I’ve gone through medical situations in my life and there were points where I tried to avoid it to not have to deal with it. And then there was a point where I couldn't not deal with it anymore. I had to pay attention to my body, and that's what I think within your work and how you use your body within space, it reminds me of how potent and powerful that being mindful of our bodies is a political act and is a way of resistance, because so much of how society is set up is not for us to have time to do that or a space to do that. So I've had to reframe the way I think about the body and paying attention to my own body as a kind of political act of resistance…

BG: Yeah, actually, my recent work is looking more closely at health like that. When I started, a lot of my works were about the bus and city building, and then I got into Negotiation. It was really just a reflection of my overall practice and how I'm thinking about the intersection of performance in the lens. But this current work, the next multi-channel film that I'm developing, is really inspired by my experience with fibroids and my first mammogram, and still thinking about interiority and relationship to environment, but specifically with the medical industrial complex and how…

HM: Sorry, those are the printed pieces right?

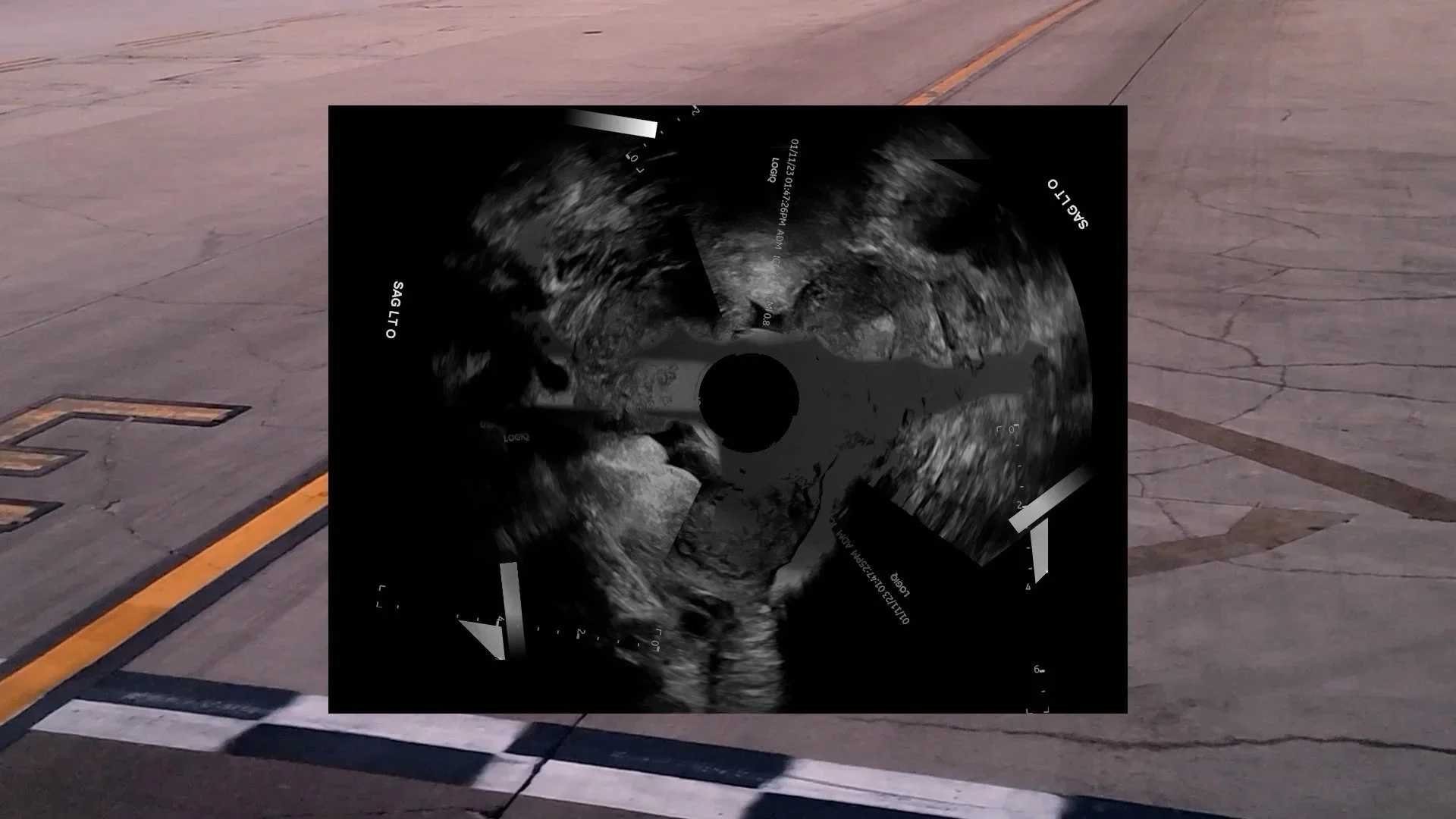

BG: Yeah I'm thinking about animation… those pieces alongside some medical images that I got that I really love. I always go back to the hospital and get the medical imaging.

HM: I didn't get to see the video Negotiation, but I did see the screen shots, and I thought I saw some X-ray images.

BG: It’s in Map to the Moon. They are ultrasounds and my mammogram scans, because they're also just fascinating images to me. I really love the conversation around photographic image making and its imperial origins, and it really being an extension of colonization as a technology, but thinking about imaging beyond the lens, and obviously that's medical imaging, like we're looking at things that we can't really see, and we're crafting these images through sound, through radiation, and through all these technologies that don't necessarily include a lens, and I’m interested in what that means, formally, conceptually, and especially with the Black image making processes and the way we consider the relationship between the visual and sound.

Map to the Moon, bree gant

HM: That’s so fascinating.

BG: I am a little obsessed. I don't have language for it, which is also why I like film, you know, as a methodology, like I don't always have language for the things I'm thinking through. And film as a thinking method, as well as dance as a thinking method, have really just saved my life as a human moving through the world.

HM: Yeah, that idea of imaging beyond the lens, it reminds me of thinking beyond words. Forming thinking into words is one process and so is image making through a lens. But then there's ways to make images beyond the lens, and there are ways of thinking beyond words. So that idea of movement and video as a form of thinking, I think, is so important as creative folk…. I really appreciate your time, bree.

BG: My pleasure, I like geeking out with fellow art nerds.

HM: Yea, it was really special to have this opportunity. To take the time to look at your work, to think through it, and the connections that you're making, or ways that you frame your work… which reminds me of a quote I found where you said “self awareness is world building,” that made me stop and think, just with how important it is to be self aware today, to be in the moment, and be within body and mind. I think so much of society is set up to not allow that to happen. I think your work is allowing people to be able to stop and consider that. That's why I appreciate your work so much, because it makes me do that.

BG: Oh, I appreciate you so much. It's an honor to be witnessed by you and have this conversation with you.

HM: I appreciate you and hopefully we get to share space again soon now that you're back in Detroit. Thank you, bye.

BG: Peace, bye.

End.