Conversation 09: Juan Carlos Rodríguez Rivera

How does one imagine a world beyond our current reality? I tend to look back into the past to grapple with this question. Learning about the past reminds me that the ground I’m standing on looked vastly different not too long ago (when you consider the grand timeline of this earth), and if that’s true, then our future doesn’t have to look anything like our present. This gives me perspective and hope. This straddling between the past, present, and future is where I see Juan Carlos Rodríguez Rivera’s work. I was able to visit Juan in Puerto Rico in November this year and was lucky to see the exhibition Images for Decolonial Futures: Antillean Continent in person. After sadly leaving the hot sun, warm sandy beaches, and echoing rhythms of Puerto Rican Christmas music, I wanted to talk to him more about the show and his artistic practice. The following Conversation covers his collaboration with Claudia Alejandra González Parrilla, the exhibition they created together, the workshops they facilitate, and Juan’s thoughts about, and hopes for, the future.

-Heather

Juan Carlos Rodríguez Rivera (Cataño, 1988) is an artist, designer, and educator. He explores new imaginaries and visual languages for/about the Caribbean through, and by, combining graphic design, speculative practices, and alternative education methodologies. His ongoing collaborative initiative, Images for Decolonial Futures, blends inhibited imagination with everyday themes to explore non-dystopian speculative futures. He is a former artist fellow for 2022 Bridging the Divides, hosted by Hunter College’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies and Princeton University, and funded by the Mellon Foundation. Recently, Juan Carlos participated in the Design Inquiry Program at Fallingwater in Pennsylvania and was part of the Haystack Open Studio Residency in Maine. Additionally, he has participated in exhibitions, workshops, and curatorial projects, at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico, Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, SFMOMA and Beta—Local. Juan Carlos holds an MFA in Communications Design from Pratt Institute in New York and is currently an Assistant Professor in the Art, Art History, and Design Department, at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan.

Heather is one half of Nox Library

Conversation with Juan Carlos Rodriguez Rivera, December 2025 (Transcript)

Note: The following conversation happened over Zoom while Heather was in Detroit and Juan was in Puerto Rico. Much of the delay and broken text has been edited and smoothed out for easy reading. Some of the connection issues have been included to remind the reader of the ongoing problems that are occurring in Puerto Rico due to a lack of infrastructural support that is exacerbated by the colonial status of the archipelago, and disastrous effects of natural resources from the “economic development” of the island.

Juan Carlos Rodríguez Rivera (JR): We lost power around 20-minutes ago. Is it okay?

Heather Mawson (HM): You're choppy.

JR: Let me wait…. It’s reconnecting… Okay, is it better?

HM: You were frozen for a second, but now you're back, and it seems better. Okay, let's get started…

JR: Don't rush me. (laughter)

HM: No, I just don't want to waste your time since you have guests.

JR: It's okay, you're not wasting my time. It's very nice to be in the AC talking to you.

HM: Thank you for agreeing to talk with me/Nox Library about your project. I'm excited to talk about the exhibition with you and share it with everyone else. Before we get into the exhibition, I wanted to talk more about your collaboration with Claudia Alejandra because from your Images for Decolonial Futures website, it looks like you've been collaborating on this project since 2023. Is that right or was it a little before that?

JR: Yeah, so I'll go back to the beginning…

HM: Because you've known each other for so long.

JR: Yeah. I think it adds to the collaboration that we went to middle school and high school together at Escuela Central de Artes Visuales, an art specialized public school. We met when I was 11, she was 12, here in Puerto Rico. We've been creating art since then, and we have always been friends and were always in contact. Then we went to different universities, she went to Mexico, I went to New York, and in 2021 that's when the collaboration started. Even though the first project was published in 2023, we started working together in 2021, after I got into the fellowship Bridging the Divides. That fellowship brought together journalists, artists, researchers, and academics to explore decoloniality; we were expanding on the definition and not just thinking about the social and political status of the island…that's another conversation, but that's when I invited Claudia.

I was like, “Hey, Claudia, I have this idea to make a project…” it wasn't called Images for Decolonial Futures at that moment—I don't remember what the name was—I’ll have to think about it. Claudia agreed, not really knowing what she was getting into. And almost five years later, here we are putting together an exhibition, but that's how we started. We decided to do illustrations and collages together, and she's like, yes, let's do it.

HM: Do you think your push to want to collaborate comes from your background in Design, or does it come from somewhere else for you?

JR: I don't think it comes from just design. I think design reinforced it. I have thought about this before and I think a lot of it comes from having five siblings. You always have to figure it out, such as how to share things or how to do things together. I think it comes from my upbringing and the school that I went to with Claudia. We were always collaborating as students. Every year we had an exhibition as a group and as a cohort we would have to figure out how to put it together—imagine 14 year old students figuring out how to put on an exhibition. So, I think that has a lot to do with it, but the part where design influenced my perspective of collaboration, is that no one's going to be wrong in this process, because we have to iterate and try things. That helps me a lot when collaborating. It’s like “yeah, let's try it, let's just see what happens, let's try that and let's try that other thing.” I’ve found that design mentality or method helps a lot with my collaborations.

HM: I'm curious, thinking about how this collaboration with Claudia started in 2021, I saw that the first workshop didn't start until 2023 on your website. But before we get into the workshops, I wanted to invite you to share more about the exhibition that you just had at Gallery Oller at the University of Puerto Rico-Rio Piedras. I know there are four different sections, can you share what those are?

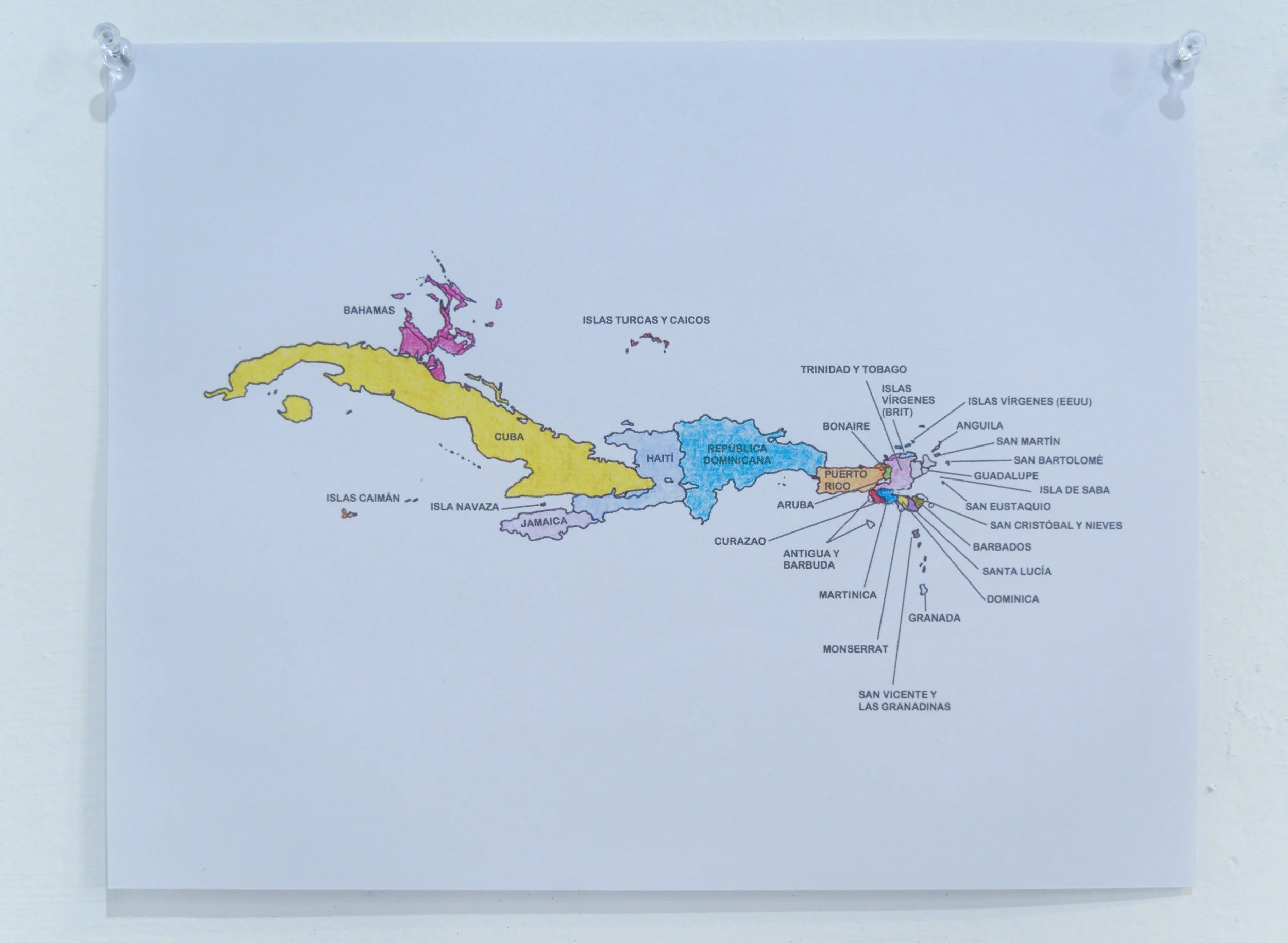

JR: The translation of the exhibition title is Images for a Decolonial Futures: Antillian Continent. It starts with an image that we created during our first collaboration when we published our first book, Puerto Rico: Imagination and Possibilities. In that publication, we had one image called the Caribbean, where we imagine an alternate reality where all of the Caribbean islands come together, like physically coming together to form a new continent, and that continent we named the Antillean continent.

In the exhibition we have four maps, and by “maps” we are also expanding that definition of maps. One is geographical, which is the expansion of that image that I was talking about; the second is a hydrographic map, where we create and explore how the rivers will come together to form a kind of circulatory system; then we have a thermal map (I think that will be the translation) which answers the question, what does does the temperature in the Antillean continent feels like in the year 3025? The fourth is a sound map that is prompted by the question, what does the continent sound like? In that piece we recorded sounds throughout the island and then we combined them with digital or glitchy audio. That map is combined with satellite images of the Caribbean. Then we close the exhibition… well, actually, there's five maps because the fifth one is a collaborative one. The last map is a self-guided workshop where people participate in imagining and contributing to their version on an Antillean continent. It's one of my favorite parts of the show right now because it prompts people to imagine and freely participate.

HM: Can you talk more about the map that prompts people to activate the space. What does that look like and what are people doing? What are the images that people are working with?

JR: One thing that Claudia and I wanted to do with our project is that every time we finish a project, we want to transform our process into some sort of methodology that other people can also recreate. It's very important to us that we understand our process so that we can invite people to participate.

The last map where people participate is a huge wall-sized printout of the Antillean continent—which is the main image of all the islands connected. The same prompts and questions that we used to create the exhibition, we are providing to the viewers or participants so that they can interact with the map. Questions like, will the continent have the longest river in the world?, what is the temperature?, and what does it sound like? In terms of materials, they have images that come from educational pamphlets that are traditionally assigned for projects in Puerto Rico to learn about culture, history, and nature. They (the images) have a very specific aesthetic and those same pamphlets were the inspiration for the first project (Cuaderno No.1). In addition to those materials, they have images that Claudia and I created. They also have pencils, pens, crayons, tape, and glue. It feels like a huge Exquisite Corpse, where some people put something, and then people add on top of that, or they expand on it.

There's a lot of sentences that are very beautiful. People have been naming things. There's a corner on the map that is called the Antillean sea and it became a beach area. Yesterday, I was giving a tour and my friend pointed out something very beautiful, someone wrote that if there's an Antillean continent, then there's a free Palestine. I thought that was so beautiful because they were thinking about the project in relation to the world. Which is kinda the goal. It's been very, very sweet and exciting to see what people are writing and reacting to.

HM: Yeah, that was a question I had in regards to the workshops. I know you've done them over many years now, and you've done them with so many different types of people, students and teachers for example. I'm curious how those demographics have shaped what comes out of the workshops. What are some difficult or rewarding things that have come up? I know you already shared some examples, but if there are any more you would like to share.

JR: I'm going to start by saying that doing workshops is so wild because the expectations are that it's something that should not be compensated for, and that a lot of times it's assumed that a workshop is easy to put together—and it's not, it’s so much work. I just wanted to put that out there.

With the workshops that we have done, because every crowd or group that we work with is very different, we have to adjust to that. I will talk about the last two workshops for example. They happened in February, and they were during the same week, or at least a week and a half apart. One was in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Puerto Rico through their educational program for high school teachers. So we were doing a workshop only for high school teachers and for most of them this was a part of their job. Some of them were super excited but others just saw it as part of their day. It's very interesting to have a group where some people are not at the workshop willingly. Of course they still participate, we still have good conversations, but it feels as they are participating because it’s part of their job..

Then we had another workshop that was open to the public where we put together an open invitation online. It happened at Beta-Local, which is an art space here (San Juan). That workshop was fascinating because I was expecting like six people to show up, and then by the end of the night, we had around 30 people participating. We had 30 people that came on their own on a Friday at 6pm and they wanted to be there. They were all different ages and from different generations. It opened up the workshop to feel kind of like a party. We learned a lot during that experience for the future—we just want to keep doing it that way.

When we bring people from different generations, those conversations are very valuable, and they shape a lot of what we've been thinking about for other projects. There is nothing wrong with having a group of teachers, it was just very specific. They teach in the same school, they teach similar classes, and they're doing this as part of their continuing education. So that felt very, very different. We have also worked with college students, which is another story. It's just different in how we use materials and depending on who is coming to the space, we change the prompts. The workshop where we didn't know who was coming, we had to improvise a bit, and maybe that also made it a bit more fun, natural, and casual.

HM: Can you share an example of one of the prompts and what was created?

JR: The workshop at Beta-Local we did in collaboration with Rafa (Dr. Rafael Capó Garcia), who's the director of Memoria (De)colonial, which is a project in Puerto Rico where they give decolonial tours in old San Juan—a very cool project. I always tell Rafa that every time you do one of those tours you start very happy and then you end very angry because you learn so many things that make you so mad and sad.

During that workshop (with Rafa) the prompt was: write your favorite Puerto Rican phrase, and then put that phrase in a bucket, and then people have to grab a phrase from the bucket (that wasn't one that they wrote) and then they take that phrase and visualize it in a speculative future. It gets very colloquial, because it's phrases that everyone knows, but then they start talking about them. Like, “oh, I wrote this, but in the future I would like this phrase to sound like this.” Let me think of an example… There's a phrase in Puerto Rico that says “a cada piojo la llega su penilla,” which translates to “every lie will get their brush.” Someone wrote that, and the interpretation of someone that lies was the piojo, which is the colonizers, and in this case, they were specifically talking about the millionaires that are moving into the island and buying everything up. So they transformed this phrase from the present and took it into the future, where Puerto Ricans were fighting against these people who want to take over the island. It was taking a little phrase from the everyday and then putting it into a wild speculative context, and then visualizing through making a collage.

HM: That’s a great example and it leads into something I've been thinking about with all of your work—this connection to decolonization and speculative imaginaries. How do you see these two things? How do you see speculative imaginaries pushing for a decolonial future? Do you feel like this is the best way to approach decolonization?

JR: I mean, I wouldn't say it's the best way. I will say it's one way and it’s one way that I'm doing it. My way of doing it comes from a reaction to questions that I was asked throughout my life. When people that don't believe, don't want to support decolonization, or don't understand are always asking for examples. “Oh, but what will Puerto Rico be like? Puerto Rico will lose this or Puerto Rico will lose that”, etc, etc. So that question, which I find very unfair, “if you want decolonization tell me what it looks like,” I find that very unfair, but then my project and my practice has been a reaction to that.

I don't know what it's going to look like, but I want to create a lot of visuals, a lot of images, a lot of imaginaries that can be answers to those questions—that become an archive, a collection of decolonial scenarios and decoloniality. The part that changes is that I’ve always been interested in the speculative, speculative design and speculative futures, because of its focus on possibilities. It focuses and invites people participating, and me as a designer/artist, to think about creating work that is not a solution, but that opens up possibilities. This liberates me from trying to define decoloniality as one thing and it opens it up for a lot of experiments.

HM: I see that kind of work also a lot in Detroit. I know you live in Detroit, but you haven’t done any work around this or workshops in Detroit, and do you see your work…

JR: Oh, wait.

HM: Are you there?

JR: Wait, we caught up for a second. Yeah, it's reconnecting… the Puerto Rican connection. (laughter)

HM: Okay, yeah, I see a lot of connections to what you just talked about and how artists are working in Detroit. Specifically, I’m thinking about the collapse of the commercial industry and artists responding to that in their work by creating speculative futures. Do you see these workshops—this work that you're doing in Puerto Rico—coming to Detroit, or are you thinking through different possibilities about approaching the Puerto Rican diaspora in Detroit?

JR: You know, I always think about Detroit. Moving to Detroit has been this experience where I keep finding a lot of commonalities with Puerto Rico. Sometimes I'm able to find and understand why I find these commonalities, and other times I just have it, and I keep thinking about them. I know we share a lot of histories, particularly when it comes to the US, the disenfranchisement, the control of money…

HM: Bankruptcy.

JR: Yeah, there's that connection, but it’s just that… I don't want to define our relationship through that. So I'm trying to figure out what else there is as a common ground. I'm going to keep thinking and working on that, but I do see a lot of connections.

In terms of the workshops, more than working with the Puerto Rican diaspora in Detroit, it's been a goal of mine and Claudia to figure how to create a version of the workshop that is responding to different contexts in collaboration with other people. We have been talking about my friends in Colombia and wondering what this would look like in Bogotá. What kind of books and visuals do they have that are equivalent to what we're using? And then make that kind of collaboration happen there. That is a dream of ours. We don't know if it's going to happen—every time we start a project the universe takes us in another direction, but it would be cool to work with someone from Detroit that is touching on or exploring similar topics, and then make new or collaborate on images for a decolonial future that is responding to that context. I find it very weird to just bring the project as-it-is to a different context, because it's designed for the archipelago, and even when we try to do it in the diaspora, it doesn't work the same way. It's a very localized project. The exhibition feels more expansive, but the workshops are very localized.

HM: Yeah, that makes sense. It also adds to what you said earlier, which is that the workshops are always changing and that they have to change based on the context that they live in.

Is there anything else that you would like to share, something you're excited about or something that you want to reflect on and leave us with?

JR: Yes, I want to share that yesterday, when I was giving a tour of the show, they pointed out so many things that I haven't seen yet. Which was so cool, because you finish something, you install it, and you see it again and again and again, so it was very exciting to see it from a different perspective. A lot of it had to do with how we are playing with water throughout the exhibition. It was a long conversation so I won't get into it too much, but from the first image that we created to the last image, there's a common thread. As the artists, we didn’t see that connection because we were just making it, making it, making it, and yeah…

HM: That’s why I feel like it’s so helpful to share what we (artists) are doing versus just making work because that can become very siloed and you get into your head about things. It’s so important to not only show, but have discussions around how the work translates. That’s why I feel like the workshops you do are so powerful because it’s one thing to make what you feel like a decolonial future will look like, but you are acknowledging that we’re connected, that we cannot create futures alone, and that we have to make them together. So it makes sense that you are continuing to learn from others and I’m sure that will continue to shape the work.

JR: It’s exciting because as much as the workshops are people creating collages on their own, they never are, they are always working with the person next to them. They are talking, sharing materials, sharing images, asking the other table for materials, and sometimes they say they want to do it together so they create a collage together.

The last thing I’ll say, because this is important for the workshops, is that the reason why we chose to do collage is because the education pamphlets that we use in elementary school are cut-up and glued onto something else. We wanted the workshops to resemble that process of cutting and pasting like we did when we were children. At the same time, for us, collaging is less threatening to people who don’t think of themselves as an artist. We are giving them a starting point, which helps a lot, so people don’t feel paralyzed. There is a parameter. All of those little things we have learned throughout the years have helped people to get started. When we started, we were just like go for it and they didn’t know where to start. So those are some reasons why we decided to focus on collage making.

HM: That’s also welcoming of you both. I’m thinking about the fact that so many people do not believe that they are creative or are not an “artist” so they don’t think that space is for them and feel intimidated. Since making is not just about the art/collage making, it’s also about the conversations that are made out of it, so pushing past the craft of it and moving towards them (the participants) being able to imagine, is a big hurdle sometimes. So it’s interesting to hear how you use the medium itself as a tool to move past that.

JR: As important as the final image that they make is, the most important part is what they start sharing with the group what they were thinking about, because then they start asking more questions and building off of one another.

HM: Love that, love some collectivism. Well thank you Juan, it was lovely talking to you more about your work.

JR: Thank you so much.

End.